How did I miss the impact on J.D. Salinger of his experiences as a soldier during World War II? As a teenager, I read pretty much the entire small canon, from Catcher in the Rye to the stories about the Glass family to Nine Stories. Most of the stories, I haven’t read since, and until a few days ago, if you had asked me how the war affected Salinger’s writing, I would have said, essentially, “Huh?”

But the experience of combat was a central experience in Salinger’s life that permeates much of his work.

Salinger in 1943 in the Air Corps

I recently re-read two stories written in the mid-1940s, For Esme with Love and Squalor and A Perfect Day for Bananafish, as well as four or five early, still-uncollected stories about soldiers. I was knocked out by the portrayal of the suffering of young combat veterans after the war. Both Seymour Glass in Bananafish and Sergeant X in For Esme would be diagnosed today with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. At least, one hopes they would be so diagnosed. Sadly, Seymour’s suicide fits right in with the frightening epidemic of suicides among young service members today.

Nine Stories by J.D. Salinger (Bantam paperback)

As a teenager reading for “universality,” I saw Seymour and Sergeant X as engaged in existential battles for purity and truth, battles that existed somewhere above the fray of concrete human experiences. The war was merely background color. Now it seems crystal clear that the characters’ experience of war and its aftermath is essential to the action and meaning of both stories.

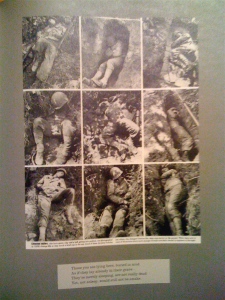

American soldiers in the Battle for Hurtgen Forest in Germany

In a 1945 letter to Esquire magazine, Salinger wrote from Germany:

“I am twenty-six and in my fourth year in the Army. I’ve been overseas seventeen months so far. Landed on Utah Beach on D-Day with the Fourth Division and was with the 12th Infantry of the Fourth until the end of the war here. The Air Corps background for This Sandwich Has No Mayonnaise [a story Esquire published] comes naturally because I used to be in the Air Corps. Have also been in the Signal Corps. Am also a graduate of Valley Forge Military Academy.”

Salinger’s yearbook entry Valley Forge

The straightforward biographical information in the letter gives no hint of the effects on Salinger of having fought in some of the bloodiest, most intense battles of the entire war. His division saw thousands of casualties as they fought their way through the Normandy landing, the Battle of Hurtgen Forest, and the Battle of the Bulge.

D-Day Landing on Utah Beach, Normandy (click to visit image website)

In August, 1944, Salinger had been among the first American troops to enter newly liberated Paris.

Allied troops enter Paris

In April, 1945, he may, according to his daughter Margaret, have helped to liberate Dachau, an experience that shocked and devastated young American soldiers completely unprepared for the horrors of the death camps.

A few months before he wrote to Esquire, Salinger had checked himself into an army hospital in Germany for psychiatric treatment. He was suffering from “battle fatigue,” the lingering effects of which he depicts in heartbreaking detail in A Perfect Day for Bananafish and For Esme With Love and Squalor.

Bananafish takes place at home, as Seymour Glass, deeply alienated and in despair, struggles to resume civilian life in shiny, post-war America, where his fellow citizens, including his young wife, are hell-bent on putting the war behind them and careening head-long into the material pleasures of prosperity.

In For Esme, Sergeant X has just been discharged from an army hospital, despite his overwhelming mental anguish and inability to function. He can’t read or concentrate, his writing is illegible, and his hands shake so much he can’t roll a sheet of paper into the typewriter to write to a friend at home. His face jumps with nervous tics, and he occasionally feels his mind “dislodge itself and teeter, like insecure luggage on an overhead rack.” He opens a parcel sent by Esme, a little girl he met before he went into combat. In it, he finds a letter and “a lucky talisman”: a shock-proof watch that had belonged to Esme’s deceased father. Holding the watch, its face cracked in transit, he feels suddenly sleepy and hopeful that he “stands a chance of again becoming a man with all his fac – with all his f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s intact.”

In both stories, the war does not end for its warriors, just because combat is over. They carry it with them out of the battlefields and into their futures. Many of today’s veterans also struggle mightily with post-combat “reintegration” (as the Army calls it) into civilian life, as the incidence of PTSD clearly indicates. But the problem doesn’t lie only with veterans or even with the inadequate response of the armed forces to the challenges faced by service members. The problem is rooted in the painful intersection of war and peace, in the uncomfortable meeting-point between returning warriors and civilians. We send young men and women off to fight, but we shy away from understanding what we are actually asking them of them. What do the words “combat”, “fight” and “war” actually mean, in the week-to-week, day-to-day experience of soldiers? What are the effects on the bodies and minds of the fighters? What are the effects on a country that turns away?

We are still not willing to face the consequences of war. They, our veterans, have no choice.

story by Melissa Cooper

Below are links to three of Salinger’s early, still uncollected stories about soldiers:

The Last Day of the Last Furlough: (Saturday Evening Post, 1944) The first story in a trilogy featuring Babe Gladwaller. Babe and his friend, Corporal Vincent Caulfield (older brother of Catcher in the Rye‘s Holden Caulfield), prepare to deploy overseas.

A Boy in France: (Saturday Evening Post, 1945) Spending a miserable night in a rain-soaked foxhole on the front lines, Babe finds solace in thinking about home and re-reading a letter from his little sister.

The Stranger (Collier’s, 1945) Vincent has been killed in the war and Babe, now home in New York City, visits his buddy’s former girlfriend to give her one of Vincent’s poems

J.D. Salinger: A Life is a new biography by Kenneth Slawenski that details Salinger’s war experiences. I have not yet read it, but you can read Michiko Kakutani’s review in the daily New York Times here and Jay McInerney’s Sunday Book Review here.