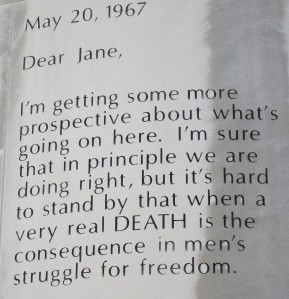

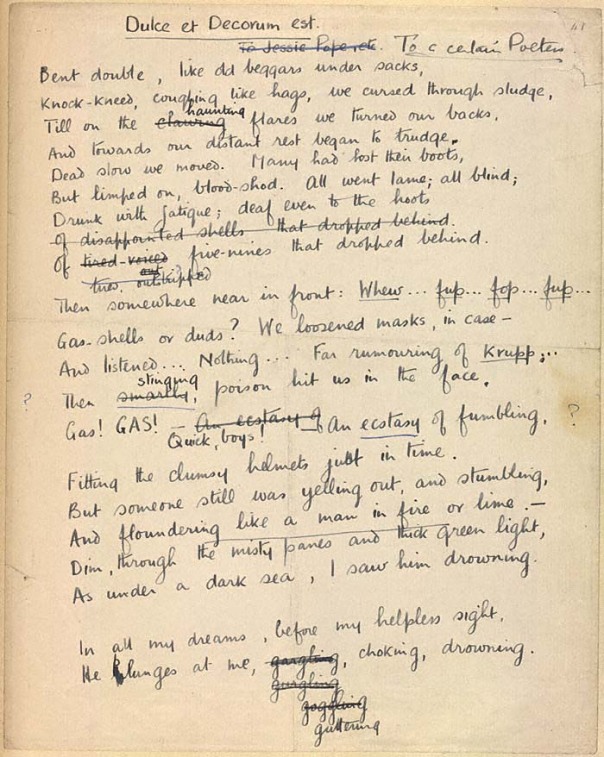

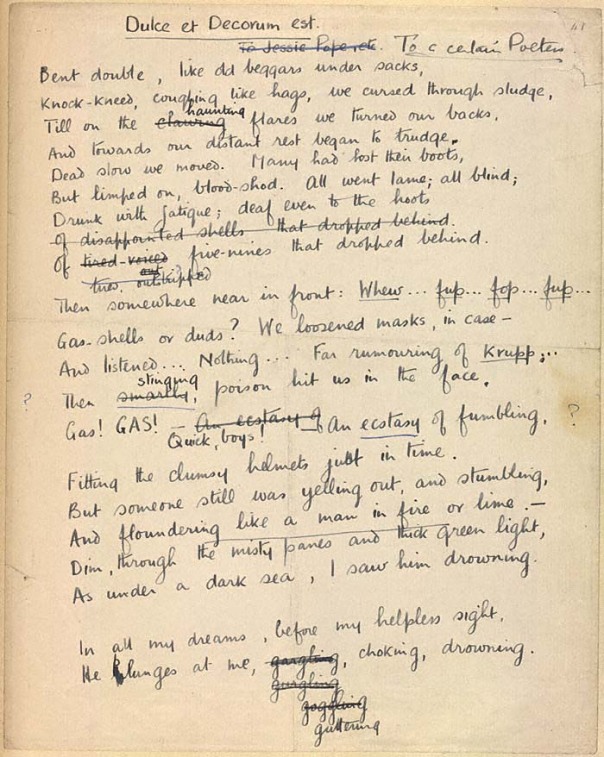

Manuscript of "Dulce Et Decorum Est" by Wilfrid Owen. Rough draft with suggested revisions by Siegfried Sassoon. (Scroll down to read finished poem.)

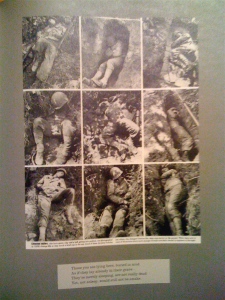

Two great British war poets, Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, both served as army officers during World War I, experiencing first-hand the horrors of trench warfare at the front and, in the case of Owen, gas attacks. Sassoon and Owen met when hospitalized for shell shock (now called post-traumatic stress disorder) in Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh. The poems reprinted at the end of this post, Sick Leave by Sassoon and Dulce Et Decorum Est by Owen, were written at Craiglockhart. Sassoon served as a mentor to the younger Owen, encouraging him and suggesting revisions to some of his poems.

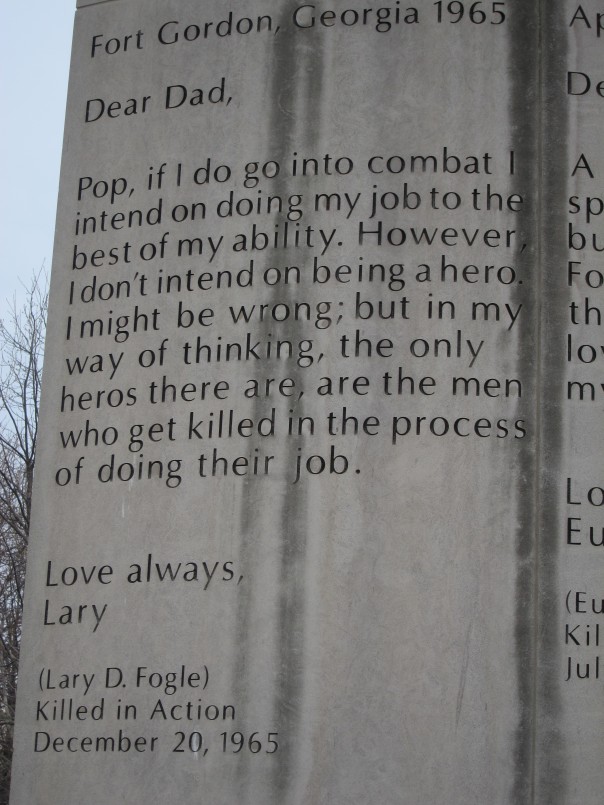

Dubbed “Mad Jack”by his men for the boldness of his exploits under fire, Sassoon came to believe that the war was an unconscionable slaughter that must be stopped.

Siegfried Sassoon. Photograph: George C Beresford/Hulton Archive

IN 1917, while back in England recovering from a shoulder wound, Sassoon, already a decorated war hero and published poet, wrote a letter of protest to his commander, Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration. With the support of prominent pacifists, including philosopher Bertrand Russell who would later go to prison for anti-war activities, Sassoon had the declaration read out in the British House of Commons and printed in the London Times. The result was a political firestorm. Sassoon was threatened with court-martial and military execution until his friend, writer-soldier Robert Graves, successfully argued that Sassoon was mentally unfit due to shell shock, or “war neurosis,” and should instead be sent for treatment to Craiglockhart.

Siegfried Sassoon, 1917, by Glyn Warren Philpot. Fitzwilliam Museum, England.

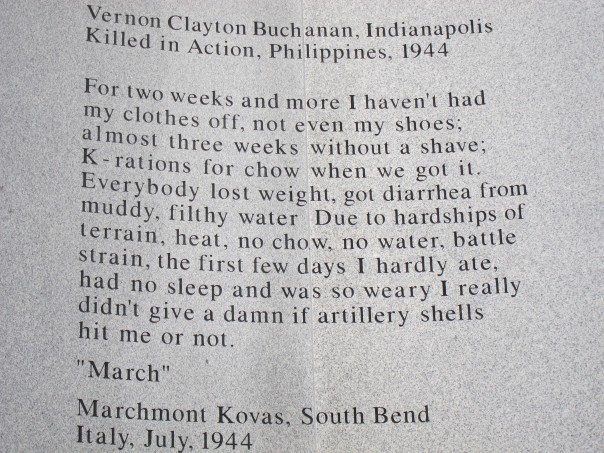

At Craiglockhart, Sassoon met Wilfred Owen, a brilliant young lieutenant who had been hospitalized after surviving numerous horrendous combat experiences, including being trapped in a trench under heavy fire for several days with the remains of a fellow officer.

Wilfred Owen

Owen was a great admirer of Sassoon’s poetry and the two became friends. Both men felt a tremendous sense of responsibility to the soldiers they had left at the front, a feeling expressed by many soldiers today when they leave a combat unit. Although both Sassoon and Owen could have avoided being sent back to action, each insisted on returning to the front. Sassoon, wounded a second time and sent home, tried fiercely to prevent Owen from returning to battle.

Owen was killed in action on November 4, 1918, a week before the Armistice. He was 25.

Ors Communal Cemetery in France, where Wilfred Owen is buried (click for image website)

Sassoon’s poem, Sick Leave, conveys the overwhelming pull of bonds of love and guilt formed on the battlefield. Owen’s Dulce Et Decorum Est describes a poison gas attack and gives a bitter twist to Horace’s ancient line (much-quoted by jingoistic writers of the time): “It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.”

Sick Leave

by Siegfried Sassoon

When I’m asleep, dreaming and lulled and warm, –

They come, the homeless ones, the noiseless dead.

While the dim charging breakers of the storm

Bellow and drone and rumble overhead,

Out of the gloom they gather about my bed.

They whisper to my heart; their thoughts are mine.

“Why are you here with all your watches ended?

From Ypres to Frise we sought you in the line.”

In bitter safety I awake, unfriended;

And while the dawn begins with slashing rain

I think of the Battalion in the mud.

“When are you going out to them again?

Are they not still your brothers through our blood?”

Dulce Et Decorum Est

by Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

****

Story by Melissa Cooper

Note: Pat Barker’s extraordinary novel, Regeneration, tells a fictionalized version of the meeting of Owen and Sassoon. Regeneration is the first book in a trilogy about the Great War that includes The Eye in the Door and Ghost Road.